To find a footing in the written

world of ethnography, I have chosen 3 texts to work through. As requested from

the syllabus, I have one book that is well known and a well-respected over view

of Moroccan culture, specifically the Berber people of North Africa. To build

on these ideas, I also chose one that is not as well-known but respected as a

reliable insight into life of Moroccan Berber women and how their work with

textiles shapes the cultural manifestations of the Berber people. For my

special topic, I have a personal interest in the work of henna and how it is used to decorate the body, and thus I have been

given the manuscript for Dr. Patricia Kelly Spurles’ doctorate dissertation on

the influence henna has in the lives of brides, gender, tourism, and women in

Morocco. I will be elaborating on this topic through readings of additional

books surrounding the art and life of henna.

Becker, C. J.

(2006). Amazing Arts in Morocco. Austin, Texas: University of Texas

Press.

|

| Berber woman holding up a hand woven floor rug |

Around the oasis of Tafilalet in Morocco, the

Berber people called the Ait khabbash weave brightly coloured carpets, shawls,

embroidered indigo head coverings, paint their faces with saffron, and wear

ornate jewelry. The symbolism in their cultural arts is heavy with

extraordinary detail, and always astonishingly beautiful - and all of it is

typically made by women. Like other Berber (Amazigh) people (not including the

Arab society of North Africa) the cultural traditions of the arts have been

entrusted to the women of their society. Through months of research living in

Morocco, and living amongst these women, Becker accumulated knowledge of the

women and their arts through family connections and female fellowships. The unprecedented

access to the artistic rituals of the Ait Khabbash resulted in a deep examination

of the arts themselves. The arts are a performance of the role women play in

Islamic North Africa life, and in many ways how women negotiate complex social

and religious issues.

Amazigh women are artists because the arts are

a form of expressing ethnic identity. The Berber women of Morocco have been

entrusted with the role of upholding the cultural traditions and identity of

their people, and the value of the Amazigh is that those who are to be the

guardians of their identity need to be the people who literally ensure that

the values and traditions are passed down from generation to generation.

Naturally this means those who create the next generation, the Amazigh women.

The arts have manifested themselves to mean visual expressions of Amazigh

womanhood, with fertility symbols prevalent throughout much of their work. The

control of the symbols of the Amazigh cultural identity has given these women

respect and prestige, with their clothing, tattoos and jewelry as statements

about identity, given publically, contrasting with the outside view that

Islamic women are secluded and veiled. However, their role as public symbols

of identity and history are not free from political influence and restriction.

With the influx of French colonialism, Arabic-dominated government, and the recent

emergence of transnational Berber movement, the women have had to adapt their

styles to an ever evolving contemporary world. By framing Amazigh arts with

cultural and historical context, it is much clearer to see the full depth and

measure of the art work of the Amazigh women.

Hoffman, K. E.

(2008). We Share Walls: Lanauge, Land, and Gender in Berber Morocco.

Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

|

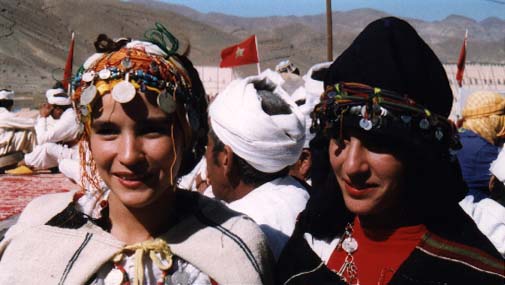

| Berber boy and girl in ceremonial dress |

The Berber people exist in southeastern Morocco, in the plains and mountains, not far from the Sahara Desert. We Share Walls explores the political

and economic shifts in the past century and how this has reshaped language

practices and ideologies of the people. With so many men leaving the rural

areas for the more urban and money lucrative regions, supposedly rich with opportunity,

the women now populate the "rugged homeland" keeping the native

language (Tashelhit) and traditions alive. The framework this creates is built

on the knowledge of rural land, people, and expressive culture - marginalized

from the evolving Arab culture of Morocco and immortalized as remnants of an

idealized past.

Through song, poetry, photographs

and text, We Share Walls closely analyses verbal and song-texted forms of

ethnography which experiences anxiety and risk within a neglected Muslim

group. Hoffman records and explains language choices and the consequences of

public and private contexts and how the Berber women accommodate themselves to

an Arabic-speaking society, while maintaining their long standing established

Berber identity. With its semiotic and gender issues bubbling just beneath the surface of social

interaction and value systems, We Share

Walls provides an eye opening insight into the culture, performance,

society and gender values of the Berber people.

Spurles, P. K.

(2002). Henna for Brides and Gazelles: Tradition, Tourism, and Gender in

Morocco.

Spending several months living

in and around Marrakesh, Morocco, researching the lives of henna artists and

the artistic designs of the Moroccan henna world, Spurles explores how women

from within the city and the surrounding country side have joined the Moroccan

tourist sector, providing henna for tourists and local women. In the 1990s,

young and old women would frequently

walk the busy tourist areas such as hotels, shopping areas and most

prominently streets and outdoor spaces looking for tourists interested in

having a piece of Moroccan art work to bring home with them on their skin.

Tourist sector henna artists worked mostly in crowded public spaces, deviating

considerably from local practices in regards to artistic composition and

placement of the henna designs, as well as from the well-known social rules

that direct the application of henna according to gender and life cycle stages.

|

| Henna: a mix of traditional andcontemporary style |

The tourist sector henna artists

are considered to be of poor quality compared to local artisan standards that

include colour and duration of the stain in addition to a complicated design

execution. Both educated tourists and local residents can distinguish the

difference in the designs applied by street-walker henna artists and traditionally

apprenticed artisans. The difference between the tourist sector artisans and

the local sector workers is so stark that local sector henna artisans would

say the tourist sector henna artists were not henna artists at all. Through

careful review of the lives of the henna artists, both local and tourist

sectors, Spurles reveals the importance henna plays in the lives of women

throughout their life time, and as a profession.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berber_people

No comments:

Post a Comment